Emma Paterson

Interview by Jennie Edgar

Photo by Dimanche Creative

February 1st, 2023

Books are about lasting encounters with language.

Emma is a literary agent living in London. She spoke with us about the impossibility of mastery, DeLillo’s Underworld, and on reading books from long ago.

“I long for the days of disorder. I want them back, the days when I was alive on the earth, rippling in the quick of my skin, heedless and real. I was dumb-muscled and angry and real. This is what I long for, the breach of peace, the days of disarray when I walked real streets and did things slap-bang and felt angry and ready all the time, a danger to others and a distant mystery to myself.”

Underworld by Don DeLillo

Tell us a little about who you are and what you do.

I’m a Literary Agent and Director at Aitken Alexander Associates. I represent writers of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which involves the discovery of new writing talent; the sale of manuscripts to publishers in the UK and the US; and the management of writers’ careers.

My passage into agenting was a traditional one: I started as a literary agent’s assistant at an agency in London called The Wylie Agency. After that I moved to Rogers, Coleridge & White, where I transitioned from the role of an assistant to an assistant building a list of clients to a fully-fledged literary agent. I joined Aitken Alexander Associates, where I now work, in 2018.

What was the first book you remember falling in love with?

The Sound and the Fury, probably. I found it at home. What interested me most as a gently precocious teenager was its difficulty. I perhaps set myself the task of mastering it, though I know now that mastery of a book is not only a narrow way to read, it is also impossible. But I was 17. A few years later, I read it five or so times at university. As trite as it sounds, it is a book that reveals itself differently with each reading.

What books have been especially meaningful to you?

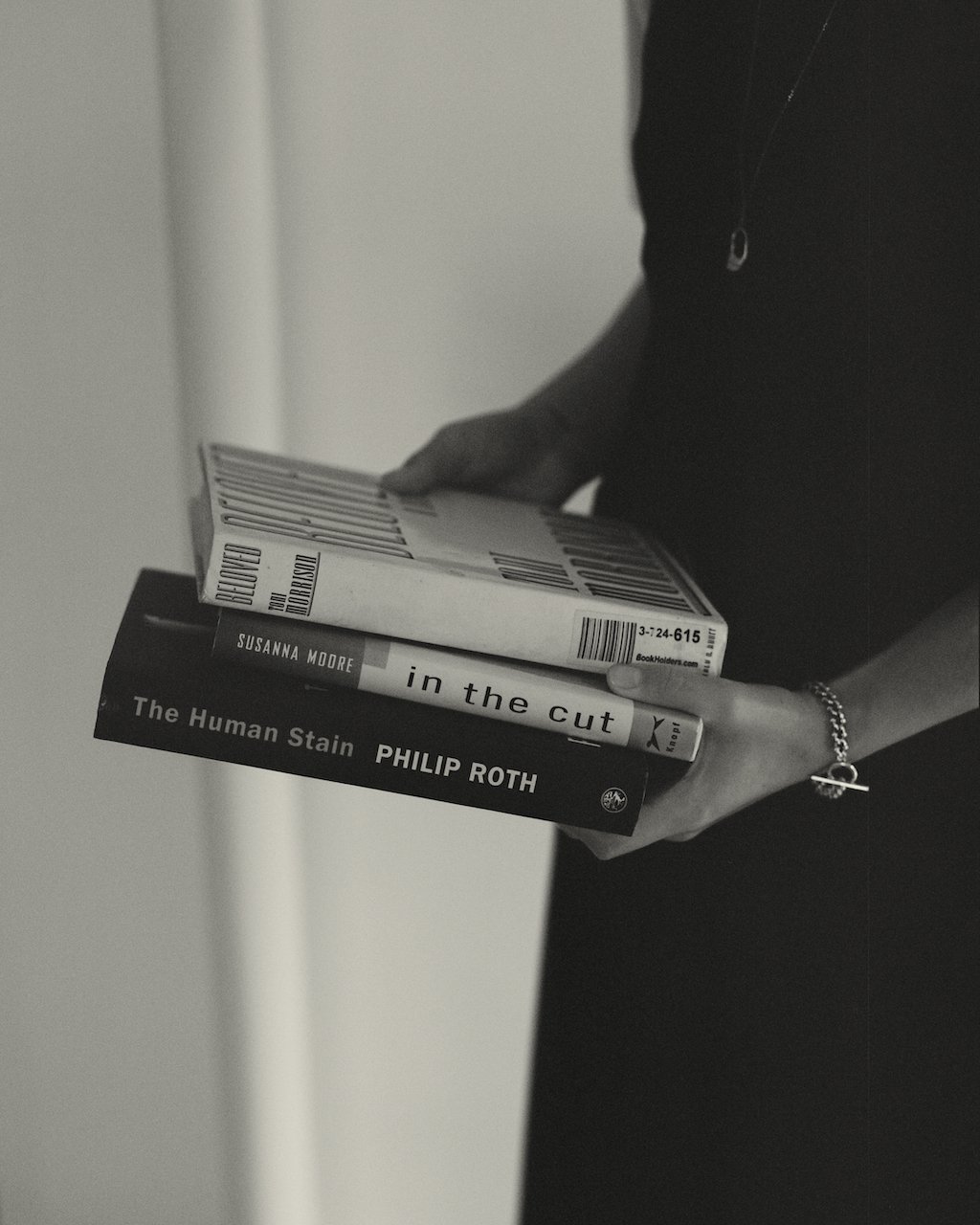

Halfway through The Human Stain, I thought to myself, this man is writing like a god, and he knows he’s writing like a god. That sounds absurd but it’s terrifically exhilarating to read a writer whose work demonstrates such self-belief, who page by page insists on it. There is a velocity to the prose that can’t be slowed, a conviction that can’t be doubted. Of course, Roth’s authority isn’t actually unquestionable. But for a moment he makes you feel as though it is, that his version of things could not be any other way.

For me, Passing is a painstaking depiction of a protagonist for whom the loss of control, and the possibility of risk, are tantamount to annihilation. I marvelled at and was devastated by Larsen’s construction of interiority. The result is a document of agitation. The prose itself frets—but so elegantly. Is that possible? In Passing, it seems possible.

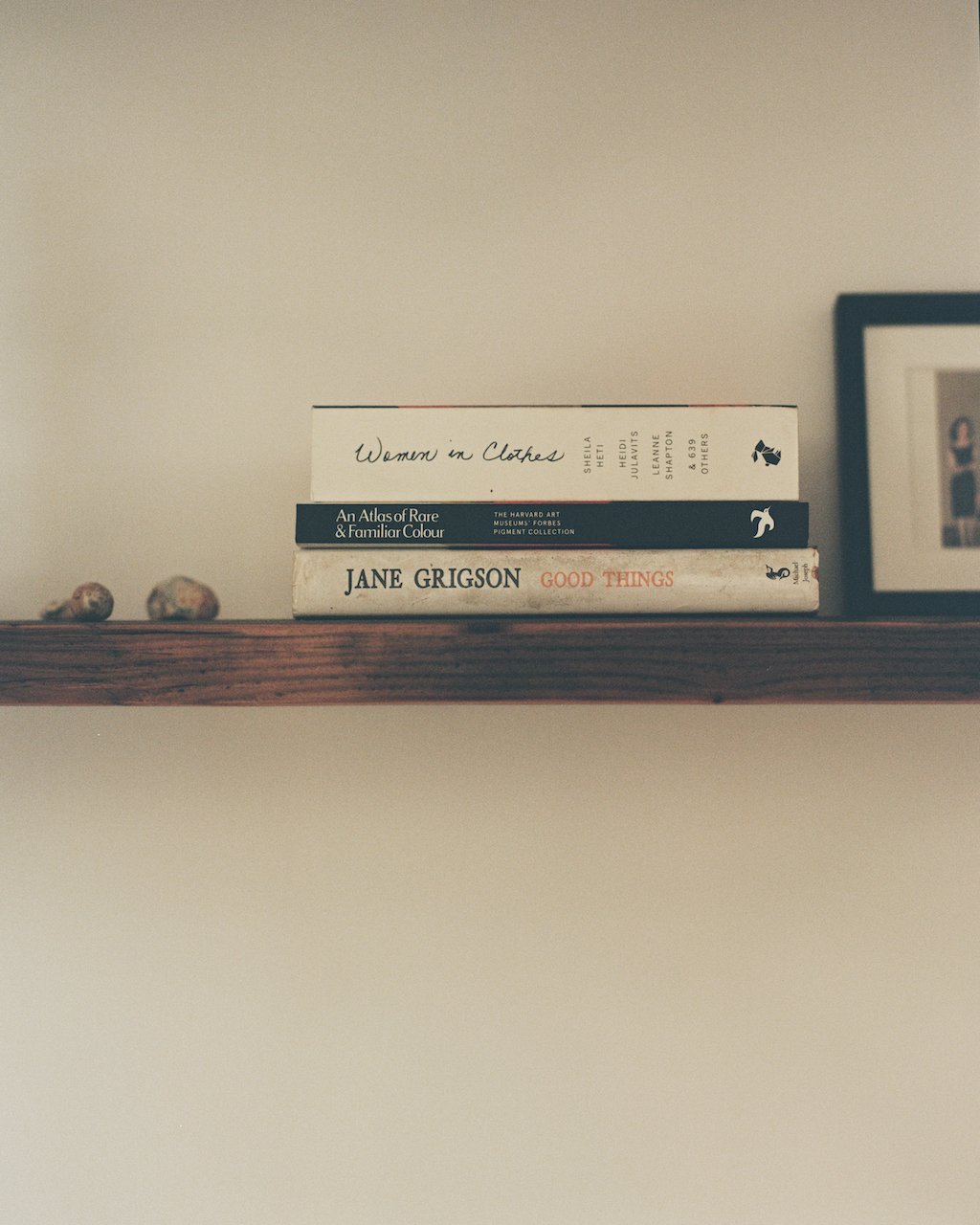

A list of other books that have been important to me are: Jane Eyre, Ariel, Less Than Zero, Beloved, Revolutionary Road, T.S. Eliot Collected Poems 1909-1962, The Wings of the Dove, Fingersmith, Gender Trouble, The Dialogic Imagination, Break It Down, Black Skin, White Masks, Light Years. More recently: A Heart So White, Passing, In the Cut, Underworld, Lost Cat, The Topeka School, Playing in the Dark, The Human Stain, The Return, Veronica, Villette.

How did the cultural resources of your childhood influence you today?

I grew up going to the cinema at least once a week, and I watched older films at home. That’s not because I was following an independently curious streak; it’s just what my parents did with their time, and I followed. Along the way, a handful of films made an indelible impression: (Douglas Sirk’s) Imitation of Life, Vertigo, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Klute, The Conversation, Alien, Kramer vs Kramer, The Silence of the Lambs, The Ice Storm, Jackie Brown, Eyes Wide Shut, The Insider. It’s an interest I carried into adulthood. This will sound silly, or implausible even, but for me, going to the cinema—to see stories made through image—is partly what makes life meaningful.

Tell us about your work as a literary agent. What most excites you?

The work I do is varied and often reactive; each day will look different depending on what I am responding to in the moment. But roughly that might mean offering editorial notes on a draft manuscript or book proposal; meeting with a publisher to talk about new authors I have taken on; negotiating financial terms with a publisher for a newly-sold manuscript; talking to an author about the cover design their publisher would like to use for their latest novel; trying to pitch myself and the agency to an author I want to work with. What most excites me is being able to share the work of an unpublished author with publishers for the first time.

What are you working on now?

At the moment I am not-patiently anticipating the delivery of several new novels from writers I already work with. I know that a handful of them will arrive soon, I know what they are about and now I am waiting for something to read.

What gives you inspiration?

The BFI just published its once-a-decade list of the 100 greatest films of all time, and that has proved enormously inspiring. It’s allowed me to see Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman in the cinema, for example—a magnificently structured film, executed with almost a surfeit of discipline. And the list led me to a beautifully bitchy book from the 1960s called The American Cinema by Andrew Sarris, in which the author dismisses an early-career Coppola as “reasonably talented”.

More generally, when things feel flat, I look to favourite artists for inspiration: Saul Leiter and his extraordinary colour photography; the breathtaking sentence craft of James Salter; the paintings of Noah Davis, studies in colour that are somehow both prosaic and mystical; any film by Sirk, Kubrick, Antonioni, Cassavetes, Yang.

Did anyone ever gift you a book that felt particularly special?

A former boss very kindly gifted me beautiful first editions of Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, but that’s because he knew I was invested in those particular novels (Less Than Zero was one of the first books I read as a teenager that captured and ennobled my generalised dissatisfaction). At the risk of sounding like an arsehole, I don’t really believe in books as gifts; I’d much rather follow my own curiosities.

“I think it’s important to read books that other people aren’t reading, at least not at the same time as you. Later, you can step into the collective, but it’s essential for me that the act of reading itself is as solitary as possible. ”

What are you looking for when you’re in search of a “good book?”

For simplicity’s sake, I’ll focus on fiction and say: language first and premise second, but not far behind. A juicy premise is important, and nothing pious. The Human Stain has an incredibly juicy premise. I am less interested in what the back cover copy might identify as the themes of the novel; they’ll reveal themselves eventually. Increasingly, I’m drawn to stories that attempt to follow the repercussions of an event or a decision or a mistake; plots that are somehow set in motion.

Undoubtedly you read a lot of books! Do you have a reading routine? How do you work it into your schedule?

When reading in my own time, and for pleasure, I tend only to read backlist. It’s a pretty inflexible rule I have; I can’t remember the last time I read a brand new book on holiday. I think it’s important to read books that other people aren’t reading, at least not at the same time as you. Later, you can step into the collective, but it’s essential for me that the act of reading itself is as solitary as possible.

I know you especially loved DeLillo’s Underworld. Can you tell us why?

It is hard not to sound annoying and self-satisfied in these conversations, and hyperbole can be very off-putting, but I had a strong instinct after reading the sixty-page prologue that Underworld would become one of my favourite books. It is an event—moral, emotional, intellectual—that threatens to overtake you. I experienced a similar certainty when I started Nella Larsen’s Passing and Susanna Moore’s In the Cut. Some books convince you from the first page, even the first paragraph, and usually that power comes from a precision and force in the language, which are qualities beyond and above just beautiful sentences. In the Cut opens with such skill: ‘I don’t usually go to a bar with one of my students. It is almost always a mistake.’ Two very spare sentences but in them there is voice, tone, past and consequence. Immediately you feel the writer’s control.

Why is reading worthwhile to you?

For me, books are about lasting encounters with language; character; place; event; drama; mystery; climax; anti-climax; humour; play; notions of time. I tend to believe that books—the best books, at least—can offer these intimacies in a way that transcends other art forms, but that is only one answer. There are other routes. From an early age, I discovered that fiction would get me there. Cinema was just as exciting. Recently, and much to my surprise, watching sport has afforded me some of the same pleasures.

What book would you like to reread?

Every year I vow to reread The Wings of the Dove. I first read it when I was 21, and I loved it, but I don’t entirely remember it. I’d like to find out whether reading it at 38 matches up with my experience of it 17 years ago. I very much doubt it.

Is there a particular author or topic you find exciting right now?

Actually, yes. I just finished The Friend by Sigrid Nunez, which is an astonishing book. A subtle book. Now I’m going back to her first novel, A Feather on the Breath of God, published in 1995. Everyone should read The Friend, a dry, sorrowful, disarming novel about grief, mortality, writing, generational shift, the fear of irrelevance, different categories of love—and sharing your life with a dog. Funnily enough, the novel was recommended to me by a trusted friend, which of course completely contradicts my usual aversion to recommendation. Anyway, it’s Nunez’s eighth book. I can’t believe I’ve not read her before now. But the beauty of a discovery like this is that there is more of her work to read; I don’t have to wait for a new novel that might never arrive.